Curating the future of precision oncology: An interview with Steve Jupe

29 Sep 2021

Steve is our Principal Curator for Actionability. His extensive career in biology and bioinformatics includes a molecular biology postdoc, bioinformatics at GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), and studying biological pathways for the Reactome project at EMBL-EBI. In 2018 Steve joined COSMIC as our Principal Curator for a new initiative, Actionability. Built on the foundations of COSMIC and linked through common mutation and disease identifiers, this new product is standalone but sticks to the core principles of quality and trusted curation by experts.

Ahead of the release of Actionability V3, I caught Steve for a quick chat to learn more about the background, process, and potential of the data.

The history of Actionability

To start at the beginning, I wanted to know the origins of Actionability - where had this innovative product idea come from?

It’s a short, simple story involving a casual conversation with COSMIC’s pharmaceutical contacts, "They told us it’s difficult to find accurate information on the impact of a mutation on the efficacy of a drug, or whether there are any drugs available, or in development, for treating people who have a particular mutation."

"So we decided to find that information."

Steve compares the ideas behind Actionability as being the same as for its ‘parent’, Core COSMIC, and the granularity with which the cancer-subtypes and mutations are defined.

"We want the same level of detail for drug efficacy. And to ask ourselves, 'has this drug ever been studied in this particular subtype of cancer?''"

A Curator’s insight

But surely that information is available already in the public domain and easy to find? I was wondering why interested parties couldn’t just use an established trials database or literature search.

As Steve explained, it’s not quite that simple, "Clinical trials databases are completed in a sort of a ‘gentlemen's agreement’ manner. The information can be incomplete, or out of date compared to what's really happening, or not showing results when they have been published elsewhere. Some trials don't appear in the databases at all.”

Typically, the priority of people running drug trials is to make treatments available to patients and to a lesser extent, publish the results in peer reviewed journals. Updating the databases isn’t high on the agenda.

"A big part of the value that I bring is looking for results of trials that become available and published that you won't find by looking at the databases. For each Actionability release, I add results to somewhere between 40 and 50% more trials than would be found in the databases alone."

Steve adds this extra value by searching for trials in the literature and interpreting them, which is no easy feat. Challenges include changes to the identifier, trial name, or patient cohort, as well as puzzling out what a study said they would measure vs. what they actually report.

"When the results come out, it's quite often only for a subset of the outcome measures or cohorts initially planned. So actually, I have to keep going back and looking. There may be subsequent publications with updates on cohorts or changes to the results. It’s a process that can literally take years and it’s my job to get the most complete picture."

To find this complete picture, he searches niche publications that don't get indexed by PubMed, conference proceedings, and even looks at the FDA label for a drug when it gets approved.

"Surprisingly, that label might be the first place where a trial is actually mentioned. It's not unheard of for a trial to not be recorded anywhere else other than the label."

Finding the ‘failures’

According to Steve, it’s quite common to find an initial paper where results look encouraging, and then later, a report that the drug wasn’t successful. Which brings us to another important feature of Actionability.

Currently, there’s no requirement for trials to publish if the results are unsuccessful or inconclusive – making it easy to miss vital data. Steve records data from the stage where the trial is first announced, "essentially before it’s even begun…", and follows it through the various stages up to completion, and publication of, results.

And if a trial gets terminated or withdrawn?

"I try and find out why - because that can be very valuable. There’s a big difference between a trial that was terminated because a patient is getting serious adverse events and a trial where the drug was withdrawn because they realised the competition had already developed something."

"That’s vital information if you’re thinking of drug repurposing. You would avoid a drug that was causing severe adverse events, but you might consider one that was withdrawn because it was no longer commercially viable."

A bit of detective work

With all this searching and deductive reasoning, I was envisioning our curators as modern day ‘Sherlock Holmes’ types. As I present this theory to Steve, he laughs - apparently ‘Sherlock Holmes’ is stretching it. But he does think the work requires a bit of deductive reasoning.

"It's often hard to work out the intentions of people running a trial. They might give you very little information, or the patient selection criteria might not be clear. If it looks like a trial is potentially interesting, and may give information, then I will include it. Sometimes they don’t pan out how I anticipated, but I think it's worth including them - they might just produce something very interesting."

Curators are also occasionally required to read between the lines and evaluate information for value. For example, what to do when two trials publish data on the same drug with conflicting results. Steve has a simple rule for these cases, "If there is conflicting evidence I use the positive result to determine the Actionability rank. But I include all data and links to trials for reference."

The units of Actionability

Moving on from detecting and onto the end-product of Actionability, I want to know what users actually ‘see’? The unit within the database is something Steve calls the ‘drug mutation disease triple’.

"I record the drug (or combination of drugs) that was used, the mutation in the patient that they're hoping to test efficacy for, and then the disease."

The triple classification – drug, mutation, disease – can then be associated with any trials Steve’s searching for.

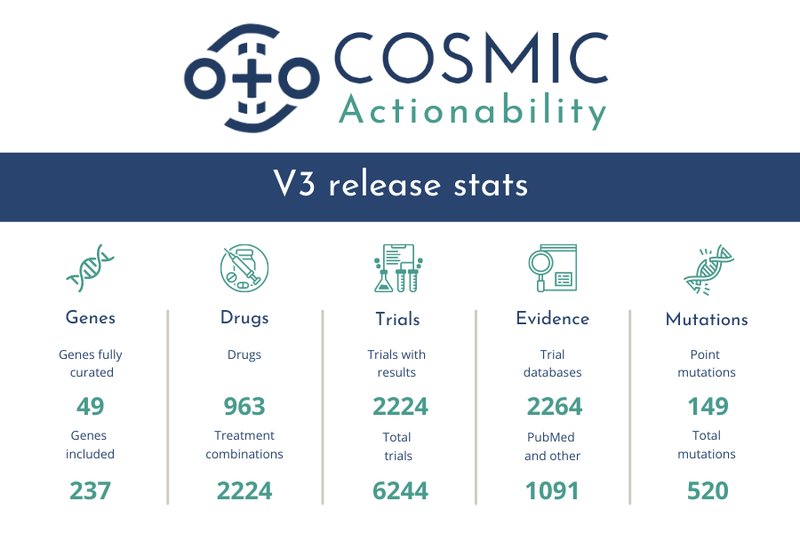

In addition, he adds in the phase of drug development, stage of progress of the trial, and number of people. A mutation might have a very different impact in people with different cancer types - and therein lies the value. Steve hunts for all trials and case studies relating to a particular mutation, "...and then the whole lot ends up being essentially a very large Excel file, which you can download."

In addition to the data, Steve assigns an Actionability ranking to the data as a combination of mutation and disease.

"I have four major categories. There are loads of systems for Actionability rankings but I’ve kept it simple. My system answers the questions; Is there an FDA approved drug that's on the market that I could give to people who have mutation X in cancer type Y? Are there any current or planned clinical trials for mutation X in cancer type Y? Are there any case studies about this drug, mutation and disease?"

"FDA approval gets a ranking of one, ongoing or planned trials are two or three, and case studies are four."

The difference between category two and three comes down to the results of studies, "…two is for late phase trials that have a clear primary outcome measure – such as progression free survival – and a statistical value that’s significant. Or in other words – drugs that look promising and likely to be on the market soon."

Watch our video for more information about Actionability

Worldwide applicability

But why use the US system over others? Because the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) can be viewed as the 'Champions League'/'Super Bowl' of the drug approval world, hence why it’s used as the gold-standard indicator for Actionability.

"I should point out, it’s not because we think drugs developed anywhere else in the world are not worthwhile. It's simply because the US is the largest market for drugs – it’s where people developing drugs want to be selling."

"But I also have a category for drugs that have been approved elsewhere in the world, but not yet approved by the FDA. I think in this coming release, I have a drug that's been approved somewhere outside the US, but not yet approved by the FDA. So there is a category for finding those and they get an Actionability ranking – look for a 1† in the table."

Valuable data

By this point, I was wondering what the extra value of Actionability could be. The benefit of this data is obvious for large-scale drug development and clinical trial design – but what about less obvious or more innovative uses?

"Two examples come to mind. First was a company using COSMIC and Actionability to create model systems that people could use for identifying new drugs – so animal models with a target mutation. I would never have thought of that."

"The second actually relates to the core COSMIC data and CRISPR-gene editing for curing diseases. Although CRISPR is very accurate, it's not 100% and might end up introducing mutations as a side effect. Our database was being used to explore if there are any mutations they ought to be avoiding and could screen for in trials. For example mutations known to cause cancers or leading to a very poor outcome for the patient."

What came next was a bit surprising to me. My understanding of large scale drug trials, particularly within the Pharma industry, is that only the ‘big dog’ cancer types are covered. The types that can make the expensive drug development process worthwhile because the market demand is so high. But Actionability may also be a tool for championing the underdog.

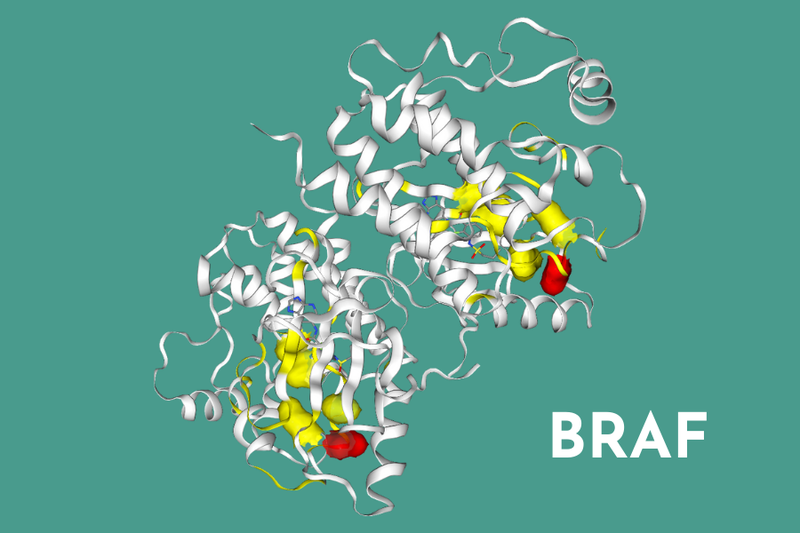

"Within Actionability, we have the big guys – the BRAFs and the BRCAs – but we also have the little guy too. They aren't as big players, but still vital for development for the future. If the overall aim is to tackle all cancers, you can't just focus on the common ones."

"I can see signs of the growing interest in a wider panel of genes, because there are more and more umbrella trials. I'll record all the information for the trial. In these cases, I’ll start off looking for information about a single gene and then end up recording information for many more."

A future within the clinical space?

It’s evident that Actionability provides a database from which people can be imaginative and ask exciting questions. But my final question relates to the present rather than the future. What about patients going through cancer right now? Could this data be used by clinicians for treatment decisions?

Steve muses for a while before answering.

"One potential use of the data is for clinicians to identify clinical trial options for patients with a particular mutation, but no current treatment. A narrative of, 'there's nothing on the market right now, but there’s an experimental drug that you could try…'"

"But obviously, to do that, you need to know where the trials are taking place. Which I don’t currently include in the download."

And here, Steve has eloquently shifted to what Actionability isn’t. It’s not intended for clinical decision making at the current time and it is not a clinically validated tool.

"Maybe we’d look at running studies in the future for the clinical applicability of this data. Thinking about the big picture, imagine a future scenario where patients have their whole genome sequenced, and given tailored prevention advice, precise diagnostics, or a precision drug regime and prognosis - giving them more time or avoiding wasted time on regimes that don’t work."

"But right now, it shouldn’t be used for diagnostic or treatment decisions."

And with that tantalising glimpse of future possibilities, I leave Steve to get on with the final updates of Actionability ahead of release.

You can learn more about Actionability and download a taster file of EGFR data here. You can purchase a licence to use Actionability via our commercial partner, Qiagen.